Axiom of regularity

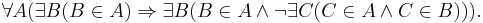

In mathematics, the axiom of regularity (also known as the axiom of foundation) is one of the axioms of Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory and was introduced by von Neumann (1925). In first-order logic the axiom reads:

Or in prose:

- Every non-empty set A contains an element B which is disjoint from A.

Two results which follow from the axiom are that "no set is an element of itself," and that "there is no infinite sequence (an) such that ai+1 is an element of ai for all i."

With the axiom of dependent choice (which is a weakened form of the axiom of choice), this result can be reversed: if there are no such infinite sequences, then the axiom of regularity is true. Hence, the axiom of regularity is equivalent, given the axiom of dependent choice, to the alternative axiom that there are no downward infinite membership chains.

The axiom of regularity is arguably the least useful ingredient of Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory, since virtually all results in the branches of mathematics based on set theory hold even in the absence of regularity (see chapter 3 of Kunen (1980)). However, it is used extensively in establishing results about well-ordering and the ordinals in general. In addition to omitting the axiom of regularity, non-standard set theories have indeed postulated the existence of sets that are elements of themselves.

Given the other ZF axioms, the axiom of regularity is equivalent to the axiom of induction.

Contents |

Elementary implications of Regularity

No set is an element of itself

Let A be a set, and apply the axiom of regularity to {A}, which is a set by the axiom of pairing. We see that there must be an element of {A} which is disjoint from {A}. Since the only element of {A} is A, it must be that A is disjoint from {A}. So, since A ∈ {A}, we cannot have A ∈ A (by the definition of disjoint).

No infinite descending sequence of sets exists

Suppose, to the contrary, that there is a function, f, on the natural numbers with f(n+1) an element of f(n) for each n. Define S = {f(n): n a natural number}, the range of f, which can be seen to be a set from the axiom schema of replacement. Applying the axiom of regularity to S, let B be an element of S which is disjoint from S. By the definition of S, B must be f(k) for some natural number k. However, we are given that f(k) contains f(k+1) which is also an element of S. So f(k+1) is in the intersection of f(k) and S. This contradicts the fact that they are disjoint sets. Since our supposition led to a contradiction, there must not be any such function, f.

The nonexistence of a set containing itself can be seen as a special case where the sequence is infinite and constant.

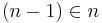

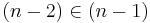

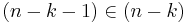

Notice that this argument only applies to functions f which can be represented as sets as opposed to undefinable classes. The hereditarily finite sets, Vω, satisfy the axiom of regularity (and all other axioms of ZFC except the axiom of infinity). So if one forms a non-trivial ultrapower of Vω, then it will also satisfy the axiom of regularity. The resulting model will contain elements, called non-standard natural numbers, which satisfy the definition of natural numbers in that model but are not really natural numbers. They are fake natural numbers which are "larger" than any actual natural number. This model will contain infinite descending sequences of elements. For example, suppose n is a non-standard natural number, then  and

and  , and so on. For any actual natural number k,

, and so on. For any actual natural number k,  . This is an unending descending sequence of elements. But this sequence is not definable in the model and thus not a set. So no contradiction to regularity can be proved.

. This is an unending descending sequence of elements. But this sequence is not definable in the model and thus not a set. So no contradiction to regularity can be proved.

Simpler set-theoretic definition of the ordered pair

The axiom of regularity enables defining the ordered pair (a,b) as {a,{a,b}}. See ordered pair for specifics. This definition eliminates one pair of braces from the canonical Kuratowski definition (a,b) = {{a},{a,b}}.

Every set has an ordinal rank

This was actually the original form of von Neumann's axiomatization. The concept of the rank of a set had also been examined by Mirimanoff Mirimanoff (1917), but that work did not consider the axiom "every set has a rank" nor the consequences of such an axiom (see Jech (2003)).

The axiom of dependent choice and no infinite descending sequence of sets implies Regularity

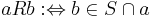

Let the non-empty set S be a counter-example to the axiom of regularity; that is, every element of S has a non-empty intersection with S. We define a binary relation R on S by  , which is entire by assumption. Thus, by the axiom of dependent choice, there is some sequence (an) in S satisfying anRan+1 for all n in N. As this is an infinite descending chain, we arrive at a contradiction and so, no such S exists.

, which is entire by assumption. Thus, by the axiom of dependent choice, there is some sequence (an) in S satisfying anRan+1 for all n in N. As this is an infinite descending chain, we arrive at a contradiction and so, no such S exists.

Regularity does not resolve Russell's paradox

In naive set theory, Russell's paradox is the fact "the set of all sets that do not contain themselves as members" leads to a contradiction. The paradox shows that that set cannot be constructed using any consistent set of axioms for set theory. Even though the axiom of regularity implies that no set contains itself as a member, that axiom does not banish Russell's paradox from Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory (ZF). In fact, if the ZF axioms without Regularity were already inconsistent, then adding Regularity would not make them consistent. Russell's paradox does not manifest in ZF because ZF does not prove that the proposed paradoxical set actually exists (e.g., ZF's axiom of separation only allows us to construct subsets of some existing set, and thus cannot be used to construct the desired set). A line of reasoning similar to Russell's paradox will, in ZF, only end up proving that the collection of all sets which do not contain themselves is not a set but a proper class (actually, the class of all sets).

Regularity and cumulative hierarchy

In ZF it can be proven that the class  (see cumulative hierarchy) is equal to the class of all sets. This statement is even equivalent to the axiom of regularity (if we work in ZF with this axiom omitted). From any model which does not satisfy axiom of regularity, a model which satisfies it can be constructed by taking only sets in

(see cumulative hierarchy) is equal to the class of all sets. This statement is even equivalent to the axiom of regularity (if we work in ZF with this axiom omitted). From any model which does not satisfy axiom of regularity, a model which satisfies it can be constructed by taking only sets in  .

.

See also

Notes

References

- Jech, Thomas (2003), Set Theory: The Third Millennium Edition, Revised and Expanded, Springer, ISBN 3-540-44085-2

- Kunen, Kenneth (1980), Set Theory: An Introduction to Independence Proofs, Elsevier, ISBN 0-444-86839-9

- Mirimanoff, D. (1917), "Les antimonies de Russell et de Burali-Forti et le probleme fondamental de la theorie des ensembles", L'Enseignement Mathématique 19: 37–52, http://retro.seals.ch/digbib/view?rid=ensmat-001:1917:19::9&id=hitlist

- von Neumann (1925), "Eine axiomatiserung der Mengenlehre", J. F. Math. 154: 219–240

External links

- http://www.trinity.edu/cbrown/topics_in_logic/sets/sets.html contains an informative description of the axiom of regularity under the section on Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory.

- Axiom of Foundation on PlanetMath